Interstate 5 in Downtown Seattle: Put a Lid on It?

An I-5 lid represents a generational opportunity to add new urban space close to downtown.

Like many American cities developed in the last century to serve the automobile, Seattle faces enormous pressure to get people out of their cars so that it can grow sustainably in the current century. That means fundamentally rethinking our highways. One possibility? Putting a lid—holding anything from park space and office towers to community space and housing—over Interstate 5 through downtown.

The idea’s most ardent supporters are found at Lid I-5, a community group led by urban designer Scott Bonjukian and architect John Feit and backed by the Seattle Parks Foundation. In 2020, a feasibility study looking at a lid over I-5 through Seattle’s downtown business district confirmed such a structure was indeed possible.

Some high-profile statewide leaders, like state senator Jamie Pedersen, have come out in support of an I-5 lid, and in fall 2023 the Seattle City Council officially endorsed exploring the concept.

Next, Lid I-5 wants the City of Seattle to tap into funding from 2021’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law that was specifically set aside to plan how to reconnect communities divided by highways.

The idea is starting to become a real possibility.

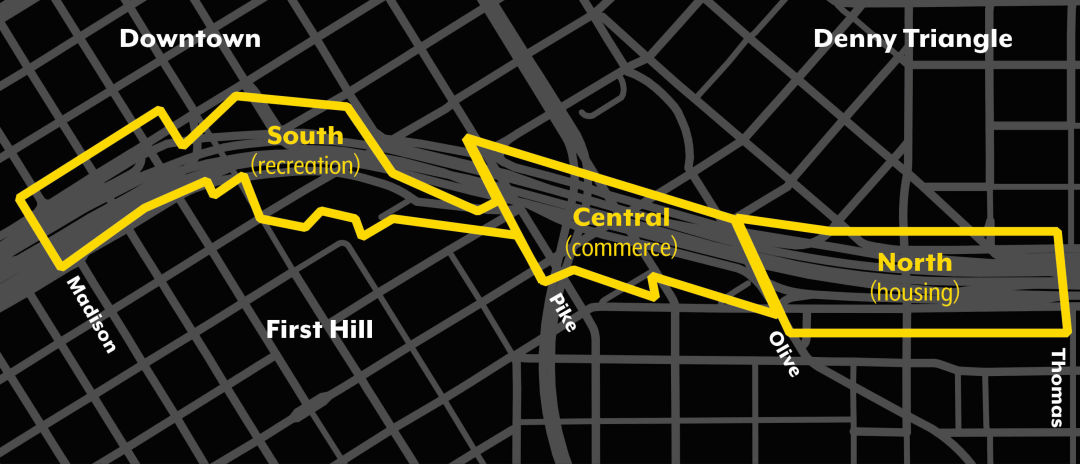

North

Some 40,000 people live within walking distance of I-5 through downtown, and a lid over the highway could reduce noise pollution and increase walkability, reconnecting nine streets that were severed when I-5 was built in the 1960s. An I-5 lid has the potential to reconnect South Lake Union and Capitol Hill, adding open space, stitching the street grid back together, and improving bike and pedestrian connections.

This could be us.

But I-5’s current ramps pose a big challenge for highway lid construction. The ramps connecting to Olive Way could require significant reconfiguration to work with a lid—which could add millions to the project’s cost. Or they could be permanently removed, with drivers rerouted to other ramps, something that might negatively impact public transit but also improve bike and pedestrian safety in the area.

Central

Seattle’s original I-5 lid was Freeway Park, one of the first highway lids in the US when it opened in 1976. It set the stage for more ambitious highway lids, like the ones over I-90 in Mount Baker, which created Sam Smith Park, and on Mercer Island, which created Aubrey Davis Park.

Covering up I-5 won't technically make the traffic disappear

But unlike in the ’70s, I-5 is now reaching the end of its design life. The highway bridges through downtown are far from contemporary earthquake-resistant standards. With the likelihood that the state will have to rebuild much of I-5 through Seattle, the conversation about lidding shifts from being about adding on top of an existing highway to building a new I-5 that achieves goals that both the state and the city have for downtown Seattle.

South

The more structures the lid needs to support, the more it would cost up front, but those structures could be leased out long-term or sold, recouping some of the lid’s construction costs. A publicly financed lid could feature park space and buildings like a downtown elementary school, something Seattle Public Schools has been exploring

for decades. But adding in commercial development and market-rate housing could

generate activity for the lid while at the same time reducing public costs.

A new lid on I-5 will have to take Freeway Park and the Seattle Convention Center into account.

A fully built-out lid could include up to 1,200 units of housing, 1.8 million square feet of office space, 200,000 square feet of retail, and 600 hotel rooms. But figuring out how to balance public benefit against these private uses is likely to prove tricky for elected officials.